Today, it is common to think of liberalism as a set of ideological values promoted during the enlightenment. Larger than life figures such as John Locke or Thomas Jefferson have been dubbed “the father of liberalism in the Classical tradition.” Perhaps the most famous of these alleged founders is the moral philosopher, Adam Smith — who will serve as our starting point for this journey.

I have chosen to begin with Smith because his ideas have arguably led to the development of three different philosophical traditions claiming to be his true heir. Conservatives, libertarians, and socialists have all argued that their system is simply the logical extension of Smith’s insights. It is with Smith that the road to liberty breaks into three paths — Where they lead, only History can tell.

Adam Smith: Philosopher, Economist, Liberal

While Smith is most famous for writing The Wealth of Nations, it was his first book, The Theory of Moral Sentiments, that pushed him into the forefront of English philosophers. Robert Heilbroner describes the book as

“an inquiry into the origins of moral approbation and disapproval. How does it happen that man, who is a creature of self-interest, can form moral judgements in which self-interest seems to be held in abeyance or transmuted to a higher plane?”

(The Worldly Philosophers. Heilbroner. 47).

Smith believed that the answer lay in what he called an impartial spectator – meaning our ability to put ourselves in the position of a neutral referee. Understanding this was not literally possible, Smith argued mankind was bound by a natural desire to love and to be lovely. In his book, Our Great Purpose, Ryan Hanley writes that

“as human beings we’ve been made in such a way that we want something more, when it comes to love, than simply getting love from others. Yes, we want to get love. But we also want to know that we really deserve to be loved even when nobody is actually giving us any”

(Our Great Purpose. Hanley. 75).

The appeal to love is not commonly associated with Smith, whose most influential work, The Wealth of Nations, has been used to promote the virtue of selfishness. His second book was rather an attempt at smashing the ideas of mercantilism. The mercantilists believed that wealth was fixed, so one nation could only grow if another declined. In their view, wealth consisted entirely of gold or silver. This is why nations would travel to faraway lands in search of gold mines. The mercantilists also sought a favorable trade balance by encouraging the exportation of goods while discouraging their importation. In his book, The Making of Modern Economics, Mark Skousen writes that

“the Scottish professor argued that production and exchange were the keys to the wealth of nations”

(TMME. Skousen. 18).

Wealth did not simply consist of how much gold a nation accumulated, but its land, houses, and consumable goods as well. Through the example of a pin factory, Smith shows how it is not a favorable trade balance or the accumulation of gold that improves the nation, but the division of labor which increases productivity and the world’s output. Thus, one country could grow without harming another.

Smith identified three main characteristics of his system of natural liberty. The first is freedom, meaning the right to produce and exchange products, labor, and capital. The second being self-interest, meaning the right to pursue one’s own business and to appeal to the self-interest of others. The third being competition, meaning the right to compete in the production and exchange of goods and services. The notion that selfishness is an important aspect of the market economy stems from these two famous passages:

“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest. […] Every individual […] who employs capital […] labours […] neither intends to promote the public interest, nor knows how much he is promoting it […] he is […] led by an invisible hand to promote an end which was no part of his intention […] by pursuing his own interest he frequently promotes that of society” (TMME. Skousen. 22).

Smith’s support for sympathy in his first book and self-interest in his second book led many German philosophers to label this apparent contradiction: The Das Adam Smith Problem. However, both Mark Skousen and Robert Heilbroner agree that a careful reading of Smith fully shows that the Das Adam Smith problem is a complete myth.

Smith’s insights are not contradictory, but actually complement one another. His argument is that man is simultaneously motivated by two competing emotions: sympathy and self-interest. For Smith, sympathy is required to forge a moral climate and just legal system which fosters an environment of competition to incentivize naturally self-interested individuals into unknowingly benefiting the common-good.

Far from an apologist for the wealthy, Smith emphasized the self-regulating aspect of the market economy because he believed it would ultimately benefit the mass of people: the consumers.

Both Skousen and Heilbroner also agree that Smith’s theories lead to a policy of laissez-faire; however, this does not mean Smith was opposed to all government action.

“[Smith] wrote of three purposes of government: ‘little else is required to carry a state to the highest degree of opulence from the lowest barbarism, but peace, easy taxes, and a tolerable administration of justice.’ More specifically, Smith endorsed (1) the need for a well-financed militia for national defense, (2) a legal system to protect liberty, property rights, and to enforce contracts and payment of debts, (3) public works – roads, canals, bridges, harbors, and other infrastructure projects, and (4) universal public education to counter the alienating and mentally degrading effects of specialization (division of labor) under capitalism” (TMME. Skousen. 33).

Smith recognized that his system of natural liberty was a double-edged sword. Self-interest was useful for pursuing wealth, but it needed to be restrained by competition and man’s natural feelings for sympathy. Government was useful for ensuring peace and justice, but it needed to be limited to allow the market system to function. In a gateway edition of The Wealth of Nations, the economist, Ludwig Von Mises, wrote:

“Smith did not inaugurate a new chapter in social philosophy and did not sow on land hitherto left uncultivated. His books were rather the consumption, summarization, and perfection of lines of thought developed by eminent – mostly British – authors over a period of more than a hundred years”

(The Wealth of Nations: Gateway Edition. Mises. V).

Rather than serving as a reactionary defense for the upper class, Smith’s work was the accumulation and summarization of a revolutionary line of thinking in defense of the common man. Both labor and capital played an important role in Smith’s theories, but the central focus of Smith’s thought is the mighty consumer.

The French Disciples of Adam Smith

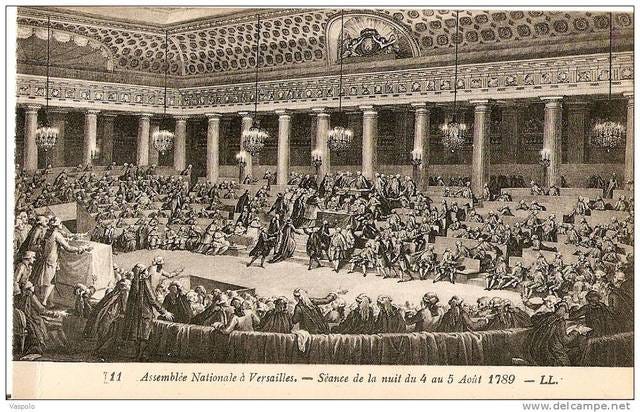

After years of bad harvests and garnering massive amounts of debt, King Louis XVI attempted to raise revenue through unpopular taxation. In 1789, he summoned the Estates General to address their financial problems. The Estates General consisted of three groups: The first made up of the Catholic Clergy, the second made up of representatives of the aristocracy, and the third representing the commoners, who characterized 95 percent of the French population. Representatives of the first and second estate would go on to join the third, declaring themselves as the National Constituent Assembly. With the assistance of Thomas Jefferson and Marquis de Lafayette, the assembly published its Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, upholding

“freedom of thought, of worship, of assembly, and from arbitrary arrest; […] enshrin[ing] equality under the law and hail[ing] private property as a basic right”

(Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 31).

The terms Left and Right can be found in the deliberations of the assemblies from 1789 to 1792. Over the course of these discussions, people began to congregate on the left or right side of the assembly. The Baron de Gauville explained:

“We began to recognize each other: those who were loyal to religion and the King took up positions to the right of the chair so as to avoid the shouts, oaths, and indecencies that enjoyed free rein in the opposing camp”

(Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 32).

Generally speaking, those seated to the left of the assembly sought to limit the powers of the monarchy, demanding an end to aristocratic privileges, and limitations to the influence of the church. Those seated to the right wished to maintain the authority of the crown, preserve aristocratic privileges, and limit qualifications for voting.

For most of history, the term liberal was used to describe the attributes of a ruling elite; In Rome, it referred to the generous and noble behavior of the citizenry. Adam Smith himself would have found it strange to identify his system of ideas under the banner of liberalism. However,

“Thanks to people like Lafayette and his circle of friends, […] a new and competing meaning of the term was beginning to spread […] us[ing] the word to describe laudable ideas, sentiments, and even constitutions. […]

The first manifestations of the word suggest that [liberal] was invented as a term of abuse. […] One of the very first instances of the word liberalism found in print is in a Spanish newspaper published very soon after the appearance of the liberal party, in 1813. […] [it] went on to explain that liberalism is a system founded upon ignorant, absurd, anti-social, anti-monarchic, anti-catholic ideas” (TLHL. Rosenblatt. 42-63).

Arguably the first liberal theorists, Madame de Stael and Benjamin Constant argued that Catholicism was an obsolete religion and hindrance to the principles of the French revolution. However, this did not suggest that religion itself was obsolete and a hindrance to their goals. Constant specifically believed that

“a liberal government could not survive without religion. […] In the end, the problem was not so much religion […] but its association with power”

(TLHL. Rosenblatt. 66-67).

The relationship between government and power is a theme that would earn Constant his rank in the liberal canon. Initially a self-proclaimed democrat and admirer of Robespierre, Constant would renounce his support for popular democracy. The reign of terror and Napoleon’s rule taught him that

“It was less the form of government that mattered […] than the amount. Monarchies and republics could be equally oppressive. It was not to whom you granted political authority that counted, but how much authority you granted. […] All the ills of the French revolution, he said, stemmed from the revolutionaries’ ignorance of this fundamental truth”

(TLHL. Rosenblatt. 66).

To curtail the abuse of authority, Constant defended freedom of thought, freedom of the press, and freedom of religion. Although religion could serve as an essential moralizing force, its purpose was corrupted when utilized by the state. Thus, he supported what is known as the separation between church and state.

Another important liberal idea at the time was the belief in free markets. Alongside Constant, liberals such as the economist Jean-Baptiste Say and the journalist Frédéric Bastiat would advocate a policy of laissez-faire, laissez-passer — meaning: let be and let pass. Otherwise known as free market capitalism.

Jean-Baptiste Say was a French economist and France’s first professor of political economy. Say became a proponent of the market economy after spending two years in London where he read Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. While he was initially a member of Napoleon’s circle, he was ousted from his position and his book, A Treatise on Political Economy, was banned for promoting laissez-faire policies. Although access to his work was restricted, the French version of his book went through four editions in his lifetime and would become a great success in the United States.

“Thomas Jefferson was so impressed with Say that he had the first English edition translated in 1821, telling his friends that Say’s book was shorter, clearer, and sounder than the Wealth of Nations”

(TMME. Skousen. 49).

Say’s book would become the best-selling economics textbook in the United States until the publishing of John Stuart Mill’s textbook after the civil war.

Despite being friends with David Ricardo, Say was a critic of many of his ideas, including Ricardo’s use of abstract reasoning and ethereal model building. A major area where Say broke with his friend was on the labor theory of value. The economist, Robert Murphy, summarizes the classical labor theory of value as the belief that

“a good’s natural price is proportional to the total quantity of labor required to produce it.”

Say rejected this idea, believing that the way consumers value a good or service determines its production. The economist Carl Menger would partake in an economic revolution that would leave behind the labor theory of value by merging Say’s subjective theory of value with what became known as the marginal theory of utility. Another one of Say’s discoveries was the concept of entrepreneurship, a term Say coined himself. Literally meaning undertaker, he emphasized the entrepreneur’s role in the economy by combining inputs of capital, knowledge, and labor to maximize profit.

“Say noted that the entrepreneur shifts economic resources out of an area of lower and into an area of higher productivity and greater yield”

(TMME. Skousen. 53).

Thus, entrepreneurship was a high-risk high-reward position that was essential for generating economic growth.

Say’s most famous contribution to economics is known as “Say’s law of markets”, or “Say’s law” for short. To understand Say’s law it is important to remember the mercantilist view that the discovery of money as well as a favorable trade balance were the key ingredients to economic growth. Utilizing the work of the economist Steven Kates. Skousen writes that

“Say attacked this scarcity of money doctrine by pointing out that it is not money that creates demand but the production of goods and services. […] Say denied that there is any general overproduction or glut in an economic downturn, but claimed that production is merely misdirected. […]

This analysis led Say to make a remarkable discovery: Production is the cause of consumption, or in other words, increased output leads to higher consumer spending. […] When a seller produces and sells a product, the seller instantly becomes a buyer who has spendable income. To buy, one must first sell. In short, Say’s law is this: Supply of X creates demand for Y” (TMME. Skousen. 55).

Say extended this analysis to argue that encouraging the production of new and improved products, rather than simply increasing consumption, is the key to economic growth. This led Say to believe that a culture of saving was beneficial rather than harmful to an economy. In his view, saving was a superior form of spending because it is used in the production of capital goods which can increase total output.

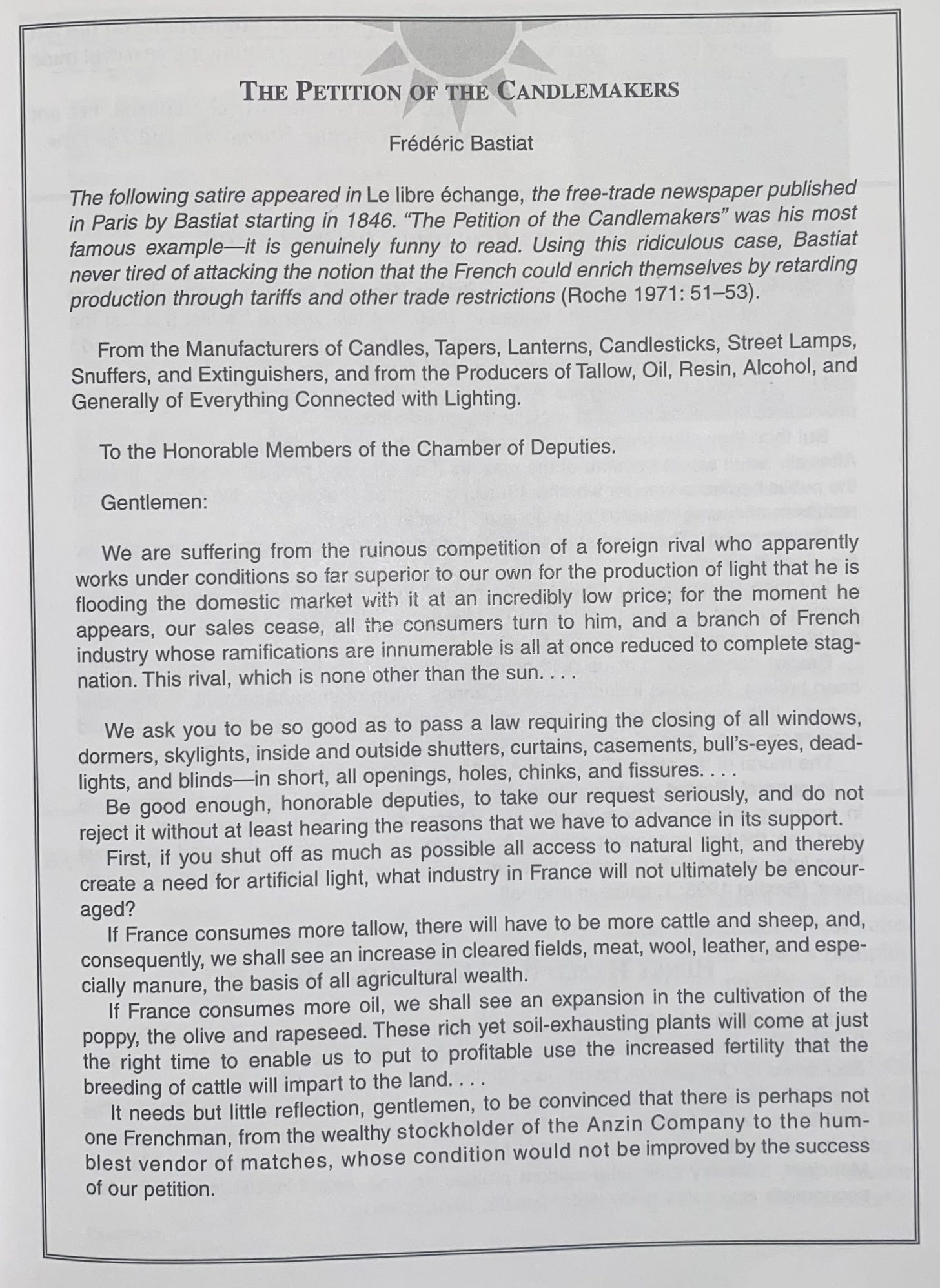

While Say was the most influential academic proponent of laissez-faire, perhaps the most vocal proponent of laissez-faire was the French journalist, Frederic Bastiat. The son of a prominent business family, Bastiat became politically involved after the 1830 revolution. During the second French Republic, Bastiat was elected to the National Assembly, where he sat on the left alongside socialists and liberals. Mark Skousen writes:

“While [Bastiat] vehemently opposed the socialists and communists policies, he felt more comfortable on the left side of the aisle, arguing against jailing socialists, outlawing peaceful trade unionism, or declarations of martial law”

(TMME. Skousen. 62).

Although their relationship soured over economic disagreements, the French anarcho-socialist (Mutualist), Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, initially wrote kindly of Bastiat, describing him as:

“an author thoroughly embued with the democratic spirit; though we cannot yet call him a Socialist, he is surely more than a philanthropist already. The clearness with which he understands and explains political economy places him ... if not far above, at least far in advance of the other economists .... Bastiat, in a word, is devoted body and soul to the Republic, to Liberty, to Equality, to Progress, as he has proved brilliantly time and again by his votes in the National Assembly.”

Under the influence of Say and Smith, Bastiat was a vocal supporter of the market economy. In 1846, he helped form a free trade association, similar to the one formed by the English trade reformists. However, unlike Say or Smith, Bastiat’s writing style made use of satire to demonstrate economic principles. In the Petition of the Candlemakers, Bastiat mocked trade protectionists who believed the French could enrich themselves by restricting foreign exchange.

In addition to his satirical work, Bastiat was also a serious legal philosopher. His most famous book, The Law, made the philosophical case for economic and political liberty. Skousen writes:

“for Bastiat, the law is a negative, [it is] a lawful defense of life, liberty, and property. The proper role of government is to defend [these] natural god given rights. […] Unfortunately, […] the law has been perverted by two causes, stupid greed and false philanthropy”

(TMME. Skousen. 63-64).

These perversions of the law are the main source of what Bastiat calls legal plunder. First, greed causes the public to plunder the fruits of others. Rent seekers hope to enrich themselves by lobbying the government to steal from the people and give to the few. In this case, the law violates property instead of protecting it. Bastiat refers to slavery and tariffs as examples of legal plunder. Second, false philanthropy, or coercive “charity” causes members of the upper class to plunder the lives of everyone else. Bastiat writes:

“We disapprove of state education. Then the socialists say that we are opposed to any education. We object to state religion. Then the socialists say we want no religion at all. We object to state-enforced equality. Then they say we are against equality … It is as if the socialists were to accuse us of not wanting persons to eat because we do not want the state to raise grain”

(TMME. Skousen. 64).

Bastiat strongly opposed the idea that government should be made up of enlightened elites who ran the lives of ordinary people. While the government may have consisted of concerned legislators, Bastiat sought to remind them that these pieces of clay they wanted to mold were intelligent and free human beings like themselves. For Bastiat, the liberal path to equality was found in liberty and the rejection of social engineering.

The Myth of Classical Liberalism

A common misconception of classical liberalism is that it stood for a unified body of ideas. Far from holding a single stance on issues, liberals varied across the spectrum. Some liberals opposed all organized religion, while others upheld religious institutions as the basis of civilization. Some liberals supported democracy, while others were indifferent to the form of government as long as it was limited. Similarly, some liberals opposed socialism, while others supported it. The utopian socialists, a name given to them by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, were a few of these early socialists who also claimed to subscribe to liberal ideals.

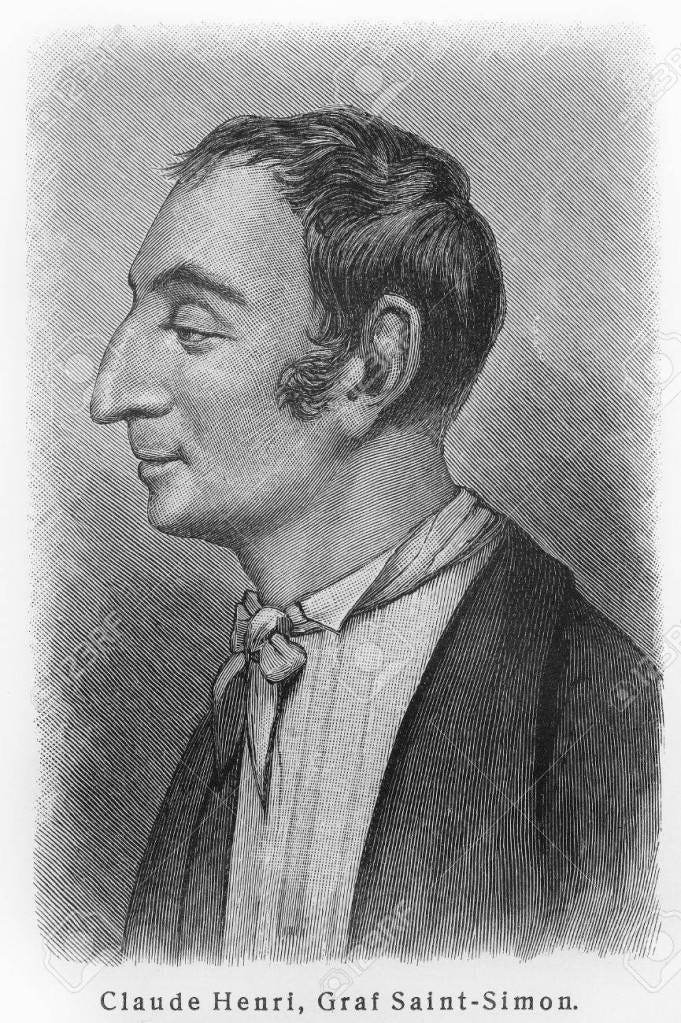

The first of the utopian socialists was a French aristocrat named Claude-Henri de Saint-Simon. As a young man, Simon went to America and participated in its great war against Britain. Years later he would return to France and support the ideals of the 1789 revolution. Simon was arrested during the reign of terror for allegedly engaging in “counter-revolutionary activity.” Simon emerged enormously wealthy after his release from prison because of the depreciation of the currency and he began working on his writings that would earn his fame as a leading socialist figure. Although he supported the abolition of inheritance, Simon did not oppose private property. Instead, he promoted public intervention in the private sector. In his book, Wrong Turnings: How the Left Got Lost, Geoffery Hodgson writes that:

“Simon called for an industrial society organized in accord with scientific knowledge. […] Influenced by Adam Smith and other economists, [he] proposed low taxes and a low level of government involvement in the economy. But he wished to minimize the destructive effects of competition, and to ensure that private businesses, guided by science, would all serve the needs of society as a whole”

(Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 63-64).

Although he disliked systems of inherited privilege, he was no fan of popular democracy. Rather, he supported a hierarchical system where managers and scientists could rise up based on their expertise to guide society. For Simon, the sole justification of government was whether or not it advanced scientific knowledge. Using the work of the economist Don Lavoie, Hodgson writes:

“although [Simon] did not advocate the abolition of private property, [he] had a crucial influence on future socialism in at least two respects. First, […] the very notion of organizing industry according to a common plan traces directly to Saint-Simon and had as its original models military and feudal organizations. Second, the elevation of science, rather than democracy or rights, as the source of guiding political principles is also traceable to Saint-Simon and had a major influence on subsequent socialism”

(Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 64).

The second of the famed utopian socialists is Francois Marie Charles Fourier. Similar to Simon, Fourier did not support the abolition of private property and never used the word socialist to describe his views. However, like Simon, he would lay the foundation for future socialist movements to come. Described by some as both a visionary and a crank, Fourier would help develop liberal insights while also making bizarre predictions about the world – such as his vision that someday the Earth’s oceans would be made of lemonade. He believed in equality before the sexes in a time when such a view was unfashionable. He also assisted in coining the term feminism itself.

“He argued that people differed in terms of their capacities and propensities. Production would be organized so that everyone would take the role most suited to his or her character. […] Conflicts of interest or preference could not be eradicated, but had to be understood and ameliorated through the creation of social arrangements that were conducive to harmony” (Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 65).

Although Fourier did not advocate the abolition of private property, he believed worker cooperatives should replace capitalist firms; a view that was expanded by Philippe Bucher but rejected by both Marx and Engels. Additionally, he was also one of the earliest supporters of a guaranteed basic income; an idea famously promoted by economists such as F.A. Hayek and Milton Friedman.

The last of the utopian socialists is the entrepreneur, Robert Owen. Most historians believe that the term “socialism” likely originated from Owen or one of his followers, and was later adopted by those sympathetic to his ideas. A devotee of Jeremy Bentham, Owen followed the utilitarian principle that argued for the maximization of happiness. One of his core beliefs was that man is a product of his environment. Like Simon and Fourier, Owen thought the application of science would remove the need for economic incentives. This led Owen to the distinctive idea that

“Virtue and happiness could never be attained in any system in which private property was admitted.”

(Wrong Turnings, Hodgson. 71).

With his personally funded experiment of New Harmony, Owen formed a communal society based on his own ideas. He denounced the continuation of familial relations as a pillar of private property. He was also wary of democracy, opposing elections as competitive and corrupting of the communal will. This caused other socialists, such as William Thompson, to denounce Owen as an authoritarian. In contrast, Owen thought of himself as a liberal visionary, creating a better world based on enlightenment principles. Although New Harmony only lasted a few years, its failure did not shake him of its ideals. He proclaimed that he

“found the population of the states far too underdeveloped at that period for the practice of a full and true social life”

(Heaven on Earth. Muravchik. 49).

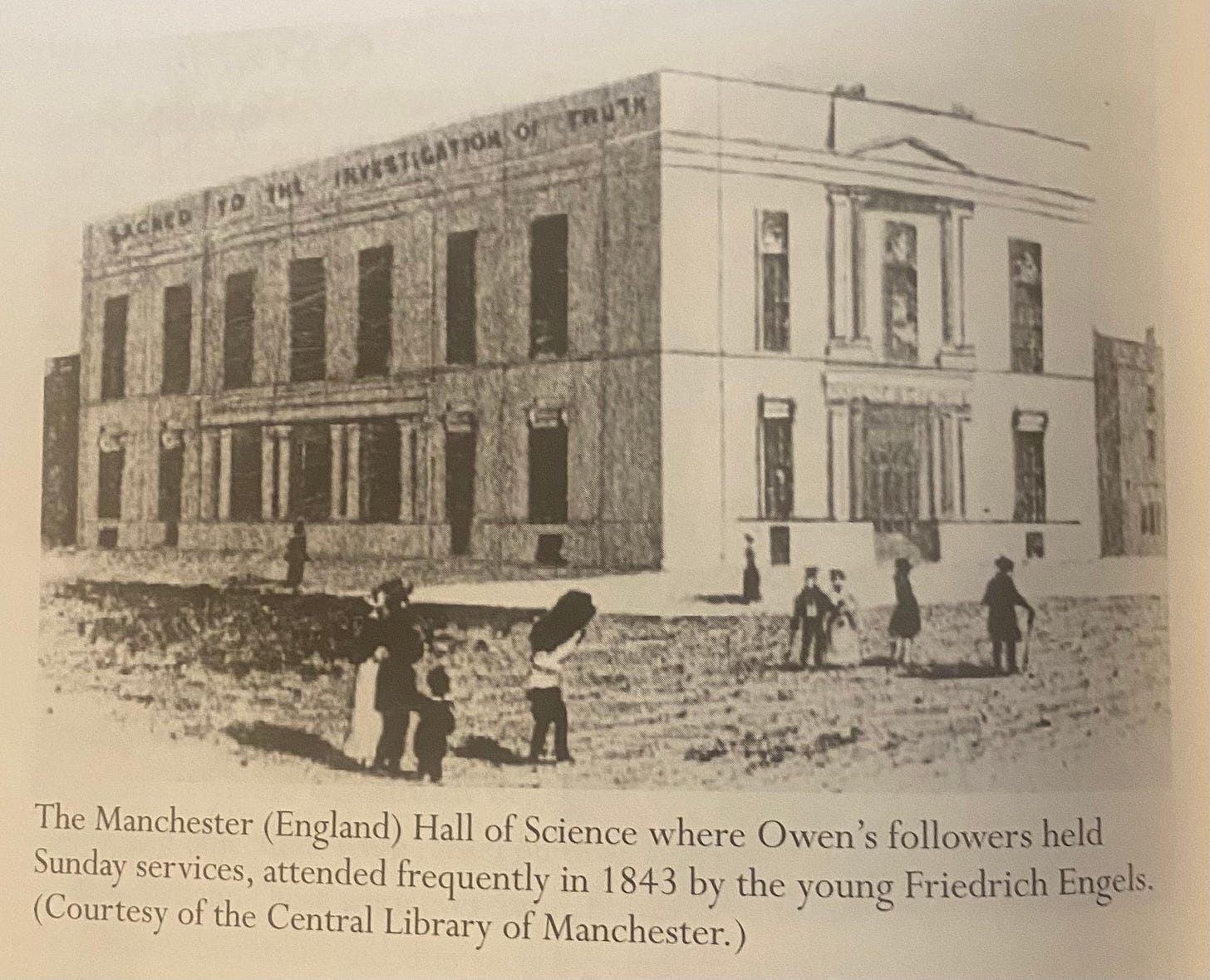

In 1835, Owen formed a new organization known as the Rational Society. Although it went bankrupt after nine years, it published millions of pamphlets and attracted thousands of followers.

From then on, socialism was almost universally defined in opposition to private property and the support of some form of common ownership. Owen himself would unknowingly influence one of the most well-known socialists in the world, Frederick Engels, who had attended one of Owen’s gatherings in 1843. Although Engels, alongside Marx, would denounce Owen as a utopian, he also declared:

“every social movement, every real advance in England on behalf of the workers links itself on to the name of Robert Owen”

(Heaven on Earth. Muravchik. 28).

The utopian socialists were not the only group challenging laissez-faire orthodoxy. Ever since the early 19th century, a strand of liberalism promoted government intervention in the economy as well as emphasizing the virtues and necessity of wealth redistribution. The American founding father Thomas Paine and the British economist John Stuart Mill best represent this common-good-liberalism.

Thomas Paine was born in England to a Quaker family. During a brief period in London, he met Benjamin Franklin who encouraged him to visit British colonial America. During his time in the colonies, Paine became a radical supporter of colonial efforts to separate from the British crown. His first book, Common Sense, served as a guide for those supporting American independence; it would also lay the foundation of Paine’s philosophy through the use of reason and human rights to approach politics. In his book, The Great Debate, Yuval Levin writes that

“as much as anyone on either side of the Atlantic, Paine had always believed the American Revolution was the beginning of a revolutionary chapter in world history. Universal principles of equality and liberty could not be held back”

(The Great Debate. Levin. 19).

Around 1788, Thomas Paine met in person with the English politician Edmund Burke, who is commonly thought of as the godfather of American conservatism. The two men got along well and formed a sort of friendship. Thomas Paine would write:

“It was natural that I should consider [Burke] a friend to mankind; and … our acquaintance commenced on that ground. […] [In a letter to a friend, Burke wrote:] I am going to dine with the Duke of Portland, in company with the great American Paine”

(The Great Debate. Levin. 1).

However, their friendship would be short lived. France was undergoing a revolution and although the Whig party of England was generally supportive, Burke was not. Yuval Levin describes Burke as an unusual Whig of his time. Instead of reformist inclinations, Burke was was inspired by the stability promoted by the Glorious Revolution. In his first book, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origins of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, Burke argued that

“human nature relies on emotional, not only rational, edification and instruction – an idea that would become crucial to his insistence that government must function in accordance with the forms and traditions of a society’s life and not only abstract principles of justice”

(The Great Debate. Levin. 6).

Following the establishment of the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, most Whigs believed the French were liberalizing their government in the model of English liberty. However, Burke was skeptical about the motives of the revolutionaries, fearing that they would bring about injustices far greater than the previous regime. The attempted assassination of the Queen of France proved to Burke that the French public was ill prepared for liberty. Like Paine, Burke feared the revolution would become a continent-wide phenomenon. This motivated him to write Reflections of the Revolution in France, his treatise against the revolution. This book would help define Burke’s conservatism as supportive of reformation when necessary but focused on the maintenance of longstanding institutions.

When news of Burkes opposition to the revolution reached Paine, who travelled to France to support its ideals, he immediately began to write a response, as did many others. His book would become the Rights of Man. Levin writes:

“leading with a systemic attempt to refute or dismiss Burke’s key points, [Paine] quickly turns to an enthusiastic case for human liberty. […] He clearly believes, as he had written in Common Sense years earlier, that we have it in our power to begin the world over again”

(The Great Debate. Levin. 33-34).

Shocked by the number of critics attacking him as an illiberal, Burke published An Appeal From the New to the Old Whigs, which emphasized many of the same points from his previous work, although more persuasively. One interesting finding is that Burke never conceded the word liberal to his critics. A friend and admirar of Adam Smith, Burke’s thought can be described as a type of Conservative-liberalism; though he never used either terms to define his ideas. During this time, Paine returned to Britain and began working on another reply, which would become a second part of the Rights of Man. This work launched a devastating attack on monarchical government – including the British monarchy. Partially a response to Paine’s writings, the

“Tory government, with significant Whig support (including Burke’s) […] enacted a proclamation against seditious writings. […] Paine, who was in London, was charged under the new law, and in September he left again for France rather than face trial”

(The Great Debate. Levin. 37).

France awarded Paine French citizenship and he was elected to the National Convention. He sat on the left side and mainly sided with the Girondins; a more moderate faction of revolutionaries as opposed to the more extremist Montagnards. An opponent of the death penalty, Paine voted for the former King of France to face banishment rather than execution. However, after the anti-Girondin coup of 1793, Paine was imprisoned and sentenced to execution. He narrowly survived due to a meeting that resulted in the guards missing his cell. Paine was released after the execution of Robespierre and returned to the United States.

Paine’s economic views are most developed in the second part of the Rights of Man and his 1797 pamphlet, Agrarian Justice. Geoffery Hodgson writes that

“Paine did not believe in laissez faire. […] Paine saw a market system as dependent on other institutions, including the state […] Paine proposed that poor relief be replaced by provision of central government funds; that state pensions be offered for those above fifty years old, rising in amount until sixty years, then to continue until death; that state provision be made for the free education of the poor; that state maternity benefits be granted to all women after the birth of a child; and that state support be provided for the young to move and find work.

He also argued that there should be a progressive taxation on landed property, coupled with the abolition if primogeniture, and a progressive tax on income from investments” (Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 52-57).

Far from being a proto-socialist however, Paine was a strong supporter of private property. Similar to Locke, Paine argued ownership becomes legitimate when it is mixed with and improved by the labor of its owner; But Paine departed from Locke after this point. While he supported private ownership of property, he did not believe the owner had full rights to all revenue granted by ownership because rightful revenues came from both labor as well as the original gifts of nature. Hodgson writes:

“For Paine, uncultivated land was a gift to all from God. […] Paine wanted to advocate the right … of all those who have been thrown out of their natural inheritance by the system of landed property and, at the same time, to defend the right of the possessor of landed property to the part which is his”

(Wrong Turnings. Hodgson. 55).

Paine’s proposal takes the form of a one-time payment once a person reaches adulthood so that they could purchase capital and become productive members of society. The English proto-socialist Thomas Spence would criticize Paine’s Agrarian Justice on the grounds that it retained the individual ownership of land.

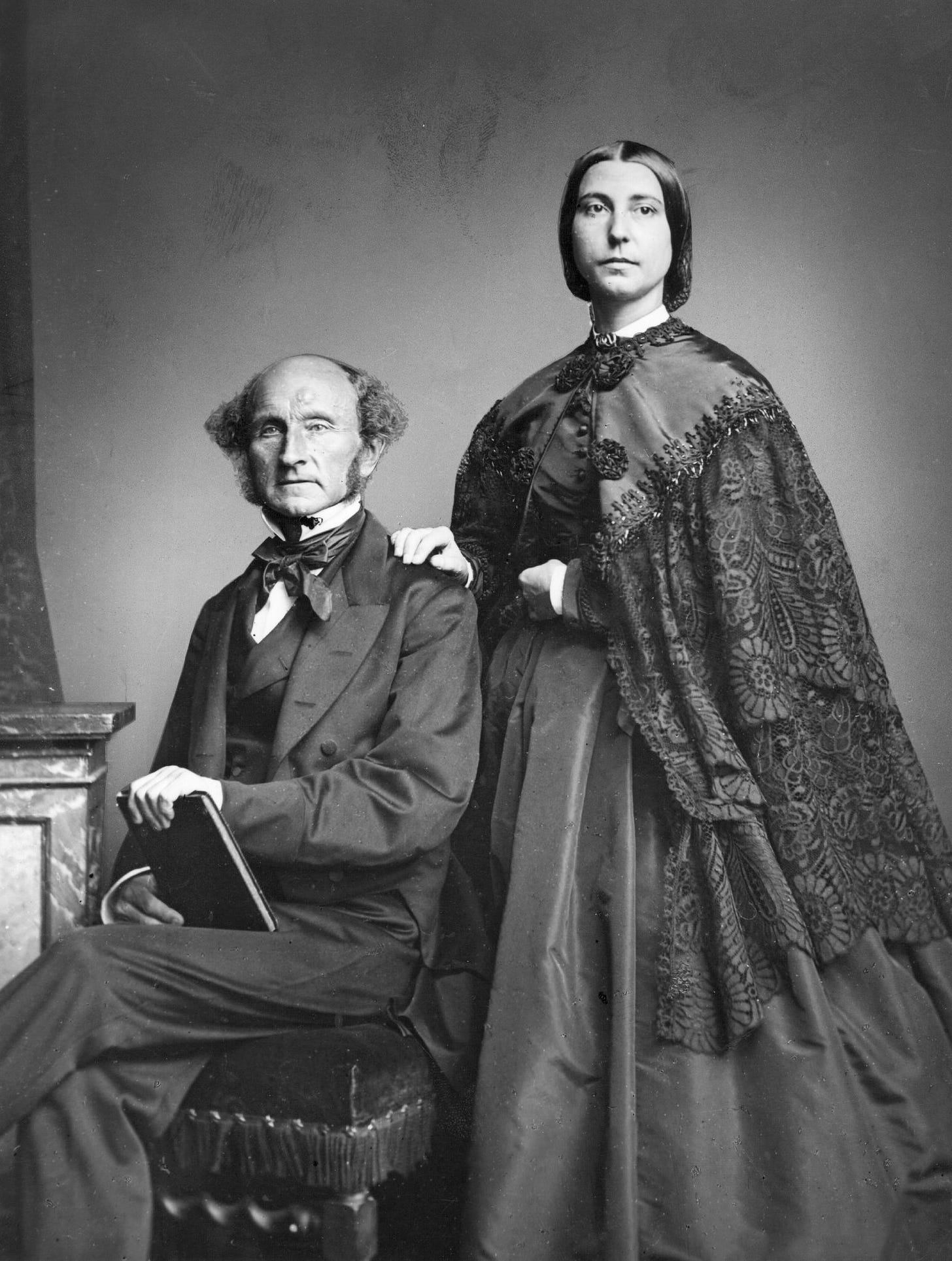

Decades later, John Stuart Mill would become the most vocal and respected proponent of common-good-liberalism.

John Stuart Mill was raised as a sort of experiment by his father, James Mill. At the age of three, the young Mill learned Greek; At the age of seven, he had read most of Plato; By the age of twelve he had mastered geometry, algebra, and differential calculus. At the age of thirteen, he created a complete survey of political economy. He had become the greatest advocate of the utilitarian philosophy inspired by Jeremy Bentham, Francis Place, and his father.

One of his most influential philosophical works is his book, On Utilitarianism. Like Bentham, Mill’s utilitarianism focused on maximizing total happiness — happiness being defined as pleasure and the absence of pain. Mill’s philosophy did not seek to maximize the happiness of a single individual, but rather that of society. Unlike Bentham, Mill did not believe happiness could be mathematically calculated; rather, he proposed a sort of smithian sympathy reliant on the social feelings of mankind. Additionally, Mill thought pleasures could be distinguished qualitatively.

“In Mill’s view, there were “higher pleasures,” small amounts of which might outweigh “lower pleasures” in the individual’s calculus. He associated pleasures with anything beyond the necessities of life (food, sleep, and so on), including learning, reading, and reflection. Thus followed his famous distinction:

It is better to be a human being dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, is of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides” (The Essential John Stuart Mill. Peart. 35).

Mill made further revision to his father’s philosophy by abandoning his belief in laissez-faire. Influenced by the work of Thomas Carlyle, the young Mill became disillusioned with free-market capitalism. This might come as a surprise to a number of people who think of Mill as a free-market icon. Did he not write the influential book On Liberty? Mark Skousen writes:

“On Liberty is a protest more against coercive moralism than against government. […] his principle theme is a rejection of Victorian attitudes—intolerance, self-righteousness, the bland uniformity of Calvinism, Puritanism, and rigid Christianity. […] Mill favored tolerance, skepticism, and free thinking”

(TMME. Skousen. 123).

While he was the very definition of a child prodigy, Mill commented that he “was never a boy” and that he “grew up in the absence of love and in the presence of fear”. He was often handcuffed, deprived of dinner, and forced to work long hours. He also suffered from a deep depression in his early twenties and contemplated suicide.

However, he regained his life after reading the works of Goethe, Wordsworth, Saint-Simon, and Josiah Warren. Their work led him away from the reactionary ideas of Thomas Carlyle, though Mill remained a critic of capitalism. Then he met Harriet Taylor, who he fell in love with, though did not marry for another twenty years because of her marriage. Once her husband died, the two immediately married; an event that estranged Mill from his family and friends. Harriet and her daughter, Helen Taylor, greatly influenced Mill’s politics. He wrote:

“Whoever, either now or hereafter, may think of me and of the work I have done, must never forget that it is the product not of one intellect and conscious, but of three”

(The Worldly Philosophers. Heilbroner. 128).

Harriet helped influence Mill to support equal rights for women as well as introduced him to more socialist literature. His book, On the Subjection of Women, was published after the death of Harriet Taylor, but clearly demonstrated her influence on him. Echoing his utilitarian ethics, Mill argues that there are no natural differences in capacity between men and women and that excluding women from public life limits the amount of talent in society and corrupts men with an unjustified sense of superiority. He also defends sexual equality as a matter of rights and Justice. He goes so far as describing sexual inequality as the last vestige of western slavery. However, Mill also argues that most women are likely to accept the traditional division of labor and that additional work outside of the household would be reserved for women without children or whose children are already grown.

“To modern ears, Mill’s defense of sexual equality may seem obvious, and, to some contemporary feminists, Mill’s criticism of sexual inequality may not be deep or consistent enough. But, when viewed in historical context, Mill’s defense of sexual equality is radical, courageous, and sometimes eloquent.”

Mill also began to think of himself as a socialist, although he was more influenced by the experimentalist utopians as opposed to the violent revolutionaries. In one passage, Mill writes:

“If … the choice were to be made between Communism with all its chances, and the present state of society with all its sufferings and injustices; if the institution of private property necessarily carried with it as a consequence, that the produce of labor should be apportioned as we now see it, […] if this or Communism were the alternatives, all the difficulties, great or small, of Communism would be as dust in the balance”

(The Worldly Philosophers. Heilbroner. 131).

However, Mill made it clear that he did not think the present state of society could remain. So, he rejected the notion that violent revolution was required to create a new socialist future. Unlike his mentor, David Ricardo, Mill believed the masses could be educated to avoid their Malthusian peril and would regulate their numbers. As a result, the accumulation process of capitalism would bid up wages, but without the introduction of an increased population, a stationary society would endure, bringing about the first stage of a benign socialism. Mill hoped that worker-cooperatives would displace privately controlled firms and predicted capitalism itself would gradually disappear.

Revolutionary socialists would prevent men such as Paine and Mill from associating liberalism with state intervention. Friedrich Engels, coauthor of The Communist Manifesto,

“denounced the ‘sham philanthropy’ and ‘sham humanity’ of liberalism, calling it a blatant hypocrisy. […] [Contemporary socialist Louis Blanc] denounced the ‘narrow anarchic doctrines of liberalism [as] the catechism of laissez-faire.”

(TLHL, Rosenblatt. 104-108).

Although liberalism fathered both interventionist and non-interventionist strands, the socialists already had a word for their ideology. To them, liberalism was just a term used by the bourgeoisie to trick the proletariat into supporting the status quo.

The Rise of Progressivism

While France, England, and America are recognized for their contributions to liberalism, Germany is often left out. It is in Germany where the term Progressive originates. In 1861, German liberals formed the Progressive Party to extend political freedom and control the Prussian budget. The most vocal liberal of these progressives was the politician, Eugene Richter. Ralph Raico writes that

“Bismarck was compelled to concede, Richter was certainly the best speaker we had. Very well informed and conscientious; with disobliging manners, but a man of character. Even now he does not turn with the wind … Another opponent, […] Theodor Heuss, admitted that Richter was the most influential leader of a determined liberalism”

(Classical Liberalism and the Austrian School. Raico. 305-306).

Richter was a strong opponent of the military state. He repeatedly criticized increases in the strength of the German military, arguing that it had worsened relations with both France and Russia. Like John Prince Smith, Richter believed in the slogan: peace through free trade. In a speech against Bismarck’s protective tariff, Richter asserted:

“Economic freedom has no security without political freedom, and political freedom can find its security only in economic freedom”

(Classical Liberalism and the Austrian School. Raico. 307).

Richter echoed these sentiments in response to rising antisemitism by branding German antisemites as

“unnational […] and damaging to our national honor. In turn, the antisemites labeled the Left-Liberals around Richter Jew-guard-troops and attempted […] to disrupt liberal meetings in Berlin through violence”

(Classical Liberalism and the Austrian School. Raico. 315).

He also opposed the anti-socialist laws passed by Bismarck to suppress the SPD — However, none of Richter’s efforts succeeded. Bismarck announced that he was not bound by constitutional authorization and chose advisors hostile to liberal ideas. After two successful wars, he suspiciously proposed that parliament should pass a law recognizing its power over spending – a move that attracted many progressives, but angered others as it would approve of his previous spendings and serve as precedent for future spending sprees. Edmund Fawcette writes that:

“Richter’s fellow liberals in parliament were most of them ready, when put to it, to scrap free-market principles if other principles promised German power and prosperity more quickly and reliably”

(Liberalism. Fawcette. 112).

Thus, the Progressive Party split into anti-Bismarck Left-Liberals and pro-Bismarck National Liberals. Members of the National Liberals included Friedrich Naumann and Max Weber. Together, they sought to unify liberalism with social democracy by working with labor movements to promote economic regulation. This led to Bismarck’s state-guaranteed social insurance for working men and women. This policy was immensely popular, and a rising class of political economists began to question the value of free markets altogether. The French economist Charles Gide went so far as to suggest gatekeeping the term liberal from thinkers such as Say or Bastiat because

“they advocated a reprehensible kind of selfishness that was blind to the public good. […] They should be called ‘modern hedonists’. [He] resolved to name them ‘classical’ or ‘orthodox’ liberals, perhaps coining those terms”

(TLHL, Rosenblatt. 224-225).

Influenced by the German welfare state, British Continental liberals also began to favor state intervention in markets, professing to follow the ideas of a “New Liberalism”. In France, Prime Minister Léon Bourgeois named this similar phenomenon “Solidarism”, which many others simply referred to as “liberal socialism”. While orthodox Marxists continued to attack the governing of the new liberals, the growth of the welfare state and the expiration of the anti-socialist laws persuaded other socialists to abandon their resentment for liberalism and seek to work within the established political order to achieve their goals. The most influential of these socialists was the former Marxist, Eduard Bernstein.

As a young man, Bernstein became infatuated with socialism following the political trial of Bebel and Wilhelm Liebknecht. This propelled him into discovering the works of Karl Marx, such as The Civil War in France. By the age of twenty-five, Bernstein was chosen as a delegate to the 1875 Gotha conference. Eventually, he began a correspondence with both Marx and Engels, befriending the two of them. After the death of Marx, Engels even asked Bernstein to take over preparation of volume four of Capital – and Bernstein was left Engel’s literary estate following his passing.

However, Tussy Marx began to express doubts in Bernstein’s motives, believing that he was beginning to deviate from orthodox Marxism following his correspondence with members of the Fabian Society, a group of non-Marxist socialists. He was deviating from orthodox Marxism, but it had less to do with the influence of the Fabian Society and more to do with the failure of Marx’s predictions. Joshua Maverick writes:

“For a time, Bernstein managed to wrestle his empirical observations into the ill-defined contours of Marxian theory. But then he tired of the labor. In a letter to Bebel in 1898, he explained: […] I wanted to save Marx; I wanted to show that he had predicted everything that had and had not happened. […] I said to myself—this cannot go on. It is idle to reconcile the irreconcilable. [… [In his book, Evolutionary Socialism,] Bernstein observed that something nearly the opposite [of Marx’s predictions] had occurred: the rich were more numerous, as were the middle classes, and the poor were better off”(Heaven on Earth. Muravchik. 101, 102, 106).

Far from rejecting all of the Marxist doctrine, Bernstein believed the growth of trade unions and democracy had weakened the power of capitalists, making it possible for the advancement of the proletariat without a revolution. In response to these developments, he

“proposed that socialists tone down their rhetoric against liberalism since liberalism was anyway evolving in the right direction. […] Democracy enabled the realization of socialism by peaceful and gradual means.”

(TLHL, Rosenblatt. 232).

In the end, Bernstein began to develop a form of Democratic-Socialism. While the Utopian Socialists thought they could simply create their own socialist societies, Bernstein thought contemporary society would evolve into a socialist one.

However, this strategy was viciously attacked by his former friends and allies. Two weeks before her death, Tussy Marx pleaded with Kautsky to persuade Bernstein away from his errors. In her book, Reform or Revolution?, the communist thinker, Rosa Luxemburg, argued that the only reason socialists should engage with established institutions is because it is

“through political and trade union activity … [that] the proletariat is brought to realize […] such activity cannot possibly bring about a fundamental improvement in their situation and that it is therefore imperative that they should, once and for all, take over the means of political power … by means of revolution”

(Heaven on Earth. Muravchik. 104).

A then twenty-nine-year-old Vladimir Lenin read Bernstein’s Evolutionary Socialism in disgust. Following the publishing of Kautsky’s refutation, Bernstein and the Social Democratic Program: An Anti-Critique, Lenin spent weeks translating it into the Russian language. Ultimately, he would become the most influential critic of Bernstein through his efforts in the October Revolution, where the Marxists finally seized political power and began constructing the first explicitly socialist state.

Unterrified Jeffersonianism

The achievement of a socialist state was not a shared vision by all critics of capitalism. The most prominent critics of state-socialism were the individualist anarchists, who were inspired by the socialist tradition launched by Josiah Warren in America and Jean-Pierre Proudhon in France. Proudhon was the first to call himself an anarchist and distinguished himself from other socialists by rejecting the very idea of state authority.

In The Nature and Destination of Government, he wrote:

“Saint-Simon, Fourier, Owen, Cabet, Louis Blanc, all partisans of the organization of work by the state, by capital, by any authority, call for, […] the revolution from above. Instead of teaching the people how to organize themselves, to appeal to their experience and their reason, they demand power from them. In what way do they differ from the despots? They are also utopian, like all despots: the latter cannot last, the former cannot take root. The implication is that the government can never be revolutionary, and for the very simple reason that it is government.”

Across the ocean, Josiah Warren independently began to develop his own anti-statism, although he never used the term anarchism. Often regarded as the American Proudhon, he rejected state-socialism due to his experience in New Harmony. Reflecting on its collapse, Warren argued its scheme of common property guaranteed

“the submergence of the individual within the confines of the community. The consequences of such a procedure […] were inevitable. Not only was individual initiative stifled by failure to provide a place within the structure for personal rights and interests beyond the sphere of religious matters, but the elimination of individual property rights resulted in almost total dissipation of responsibility for the occurrence of individual capacity, failure, and short-comings of other kinds.”

Still an advocate of the labor theory of value, Warren thought labor ought to exchange for labor; or that cost should be the limit of price. In his view, this made it impossible for one person to live off the labor of another without their knowledge and consent. Alongside Stephen Pearl Andrews, they created the voluntary community, Modern Times, where they utilized labor notes, a form of money which allowed people to trade their labor for the labor of others. However, the community began to disintegrate as the U.S. approached civil war.

In 1871, Josiah Warren attended a lecture where he met an eighteen-year-old Benjamin Tucker. Alongside Lysander Spooner and Voltairine de Cleyre, the three would come to define American Individualist anarchism as a form of laissez-faire socialism. Although he would abandon the term socialism later in his life, the early portion of Tucker’s career was spent defending it against state-socialists. He defined state-socialism as

“the doctrine that all the affairs of men should be managed by the government, regardless of individual choice. […] Anarchism […] may be described as the doctrine that all the affairs of men should be managed by individuals or voluntary associations, and that the state should be abolished. […] The Anarchists are simply unterrified Jeffersonian Democrats”

(Markets Not Capitalism. Edited by Chartier & Johnson. 24, 26, 31).

Like other socialists, Tucker considered his anti-capitalism to be a strident opposition to monopoly; However, he also thought of his socialism as a radical and consistent laissez-faire. Rather than remedying market monopoly with state monopoly, Tucker argued market monopoly could only originate from the existence of state monopoly.

He had four types of state monopoly in mind: (1) The money monopoly. This consists of the privilege by the state for certain individuals to issue currency. (2) The land monopoly. This is comes from the enforcement of land titles which do not rest upon personal occupancy and cultivation. (3) The tariff monopoly, which imposes a tax on cheaper goods and services. (4) The patent monopoly, which protects inventors from competition. Tucker concludes his essay, State Socialism and Anarchism, with the writing of Ernest Lesigne.

“There are two socialisms. […] One is dictatorial, the other libertarian. […] One wishes all monopolies to be held by the state; the other wishes abolition of all monopolies. […] The first has confidence in social war. The other believes only in the works of peace. […] Both declare that the existing state of things cannot last. […] The first will fail; the other will succeed.”

In his book, Radicals for Capitalism, the libertarian writer, Brian Doherty, describes Benjamin Tucker’s greatest contributions to the individualist anarchist tradition as

“Publishing in Liberty and befriending the nineteenth-century individualist anarchist most revered by modern libertarians: Lysander Spooner”

(Radicals for Capitalism. Doherty. 48).

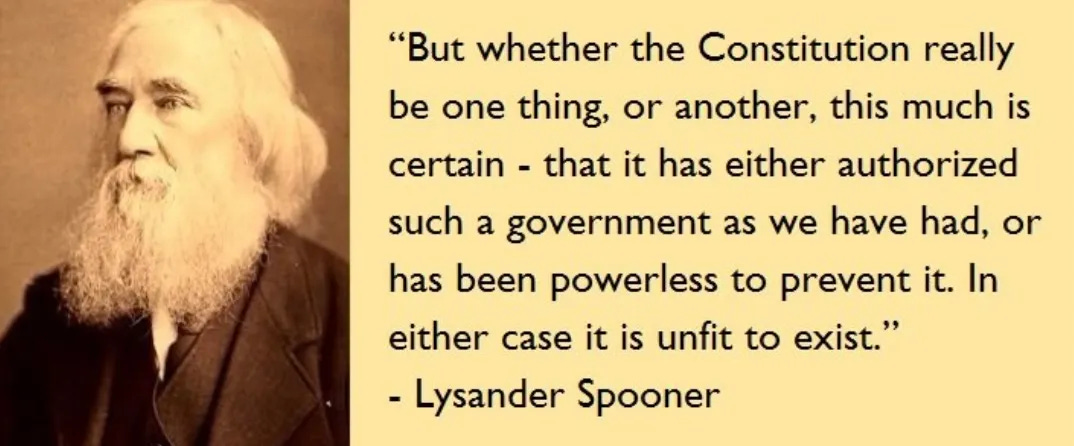

Born in 1808 on a farm in Massachusetts, Spooner’s life would include: battling the U.S. Post office, befriending John Brown, and refuting the authority of the U.S. constitution. Back then, the government subsidized the infrastructure used by mail couriers and the postage rate covered the cost of these subsidies. Spooner believed the U.S. postal monopoly was unjust and announced the creation of the American Letter Mail Company to compete with the government. In his pamphlet, The Unconstitutionality of the Laws of Congress, Prohibiting Private Mails:

“He argued that although the Constitution granted Congress the power to “establish post offices and post roads,” this only gave Congress the authority to create a postal service, not to prohibit competition.”

The government was eventually able to shower him with legal expenses that forced Spooner to abandon his business. However, the most important legal issue of his time was the issue of race-based-slavery.

Unlike most abolitionists, who sought pragmatic means to gradually weed out slave society, Spooner believed white northerners should invade southern plantations and free as many slaves as possible. He even played a small part in the Secret six conspiracy — which financed John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry. After its failure, Spooner offered his talents as an attorney to the secret six and devised a scheme to free Brown from prison.

Another contemporary of Spooner was the famous abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison, who is known for burning copies of the constitution — declaring it a pact with Satan. However, In his pamphlet, The Unconstitutionality of Slavery, Spooner made the argument that the constitution actually opposed slavery. Randy Barnett argues that Spooner’s defense of the constitution is grounded on the idea of natural law. He writes:

“It would seem that the argument against slavery that follows from Spooner's views ofnatural law and natural rights is obvious and almost trivial. (1) Written laws, including written constitutions, that violate natural justice as defined by natural rights are not to be enforced by judges. (2) Slavery is unjust because it violates the natural rights of the slave. Therefore, (3) slavery is unconstitutional and not to be enforced by judges.

Yet, despite the fact that Spooner would have accepted this syllogism as sufficient to condemn slavery, this was not the principal method of constitutional interpretation he brought to bear on its constitutionality. "I shall not insist," he wrote, "upon the principle ... that there can be no law contrary to natural right; but shall admit, for the sake of argument, that there may be such laws.

From this interpretive starting point, we can now see Spooner's basic strategy for finding slavery unconstitutional.

To assert, therefore, that the constitution intended to sanction slavery, is, in reality, equivalent to asserting that the necessary meaning, the unavoidable import of the words alone of the constitution, come fully up to the point of a clear, definite, distinct, express, explicit, unequivocal, necessary and peremptory sanction of the specific thing, human slavery, property in men. If the necessary import of the words alone do but fall an iota short of this point, the instrument gives, and, legally speaking, intended to give, no legal sanction to slavery.

Now, who can, in good faith, say that the words alone of the constitution come up to this point? No one, who knows anything of law, and the meaning of words. Not even the name of the thing, alleged to be sanctioned, is given. The constitution itself contains no designation, description, or necessary admission of the existence of such a thing as slavery, servitude, or the right of property in man. We are obliged to go out of the instrument, and grope among the records of oppression lawlessness and crime-records unmentioned, and of course unsanctioned by the constitution -to find the thing, to which it is said that the words of the constitution apply. And when we have found this thing, which the constitution dare not name, we find that the constitution has sanctioned it (if at all) only by enigmatical words, by unnecessary implication and inference, by innuendo and double entendre, and under a name that entirely fails of describing the thing.

Everybody must admit that the constitution itself contains no language, from which alone any court, that were either strangers to the prior existence of slavery, or that did not assume its prior existence to be legal, could legally decide that the constitution sanctioned it. And this is the true test for determining whether the constitution does, or does not, sanction slavery, whether a court of law, strangers to the prior existence of slavery or not assuming its prior existence to be legal-looking only at the naked language of the instrument-could, consistently with legal rules, judicially determine that it sanctioned slavery. Every lawyer, who deserves that name, knows that the claim for slavery could stand no such test.”

Although Garrison remained unpersuaded by Spooner’s argument, he welcomed fellow abolitionists to utilize it. In Reason Magazine, Damon Root writes:

“Among those who adopted Spooner's argument was Frederick Douglass. […] In an 1851 editorial he said "a careful study of the writings of Lysander Spooner" prompted him to change his mind. "Take the Constitution according to its plain reading," Douglass told the Rochester Ladies Anti-Slavery Society on July 5, 1852. "I defy the presentation of a single pro-slavery clause in it." In fact, Douglass told the crowd, "Interpreted as it ought to be interpreted, the Constitution is a glorious liberty document."

Spooner is also known for advocating what is today known as jury nullification. In his longest work of legal scholarship, Trial by Jury, he made the argument that juries were not simply meant to decide whether or not a defendant broke the law:

“Even if the defendant did perform the alleged act, the jury must have the power to decide to refuse to convict anyway, […] to nullify the conviction”

(Radicals for Capitalism. Doherty. 50).

Spooner would abandon his defense of the constitution after the American civil war. Although he was one of the most radical opponents of slavery, he disagreed with the North’s argument that the south was permanently bounded to the constitution.

In his most libertarian work, No Treason: The Constitution of No Authority, Spooner launched an assault on the idea that people were bounded to government by a social contract. He believed that only consent could give moral validity to state force and that those who did not explicitly consent to the constitution owed it no allegiance — hence the title of the piece, No Treason. In a popular passage, Spooner tries to prove why the state has a lower moral standing than a common thief:

“The fact is that the government, like a highwayman, says to a man: Your money, or your life. ... [But] the highwayman . … does not pretend that he has any rightful claim to your money, or that he intends to use it for your benefit. … He has not acquired impudence enough to profess to be merely a "protector."... Furthermore, having taken your money, he leaves you.

… He does not persist in following you on the road, against your will; assuming to be your rightful "sovereign" on account of the "protection" he affords you. He does not keep "protecting" you, by commanding you to bow down and serve him; by requiring you to do this, and forbidding you to do that; by robbing you of more money as often as he finds it for his interest and pleasure to do so; and by branding you as a rebel, a traitor, and …shooting you down without mercy, if you dispute his authority, or resist his demands.

He is too much of a gentleman to be guilty of such impostures, and insults, and villainies as these. In short, he does not, in addition to robbing you, attempt to make you either his dupe or his slave” (Radicals for Capitalism. Doherty. 51).

Some people have questioned whether Spooner really qualifies as an individualist anarchist or is simply a limited government libertarian. He never identifies with either term and his writings leave open the idea that government could be justified if it is voluntarily funded by its citizenry. However, another one of his contemporaries would leave no doubt in her strict opposition to the state.

Voltairine De Cleyre was born in 1866 to a liberal family — her father even named her after the french philosopher Voltaire. Against her wishes, her father sent her to a Catholic school at the Convent of Our Lady of Lake Huron. Even though she detested the school, she excelled in her academics and became equated with the free-thought movement which further radicalized her atheism and introduced her to many socialist thinkers. The specific event that converted her to anarchism was the Haymarket affair of 1886 that resulted in the execution of four innocent men.

“Glimpsing the newspaper headlines — "Anarchists Throw Bomb in Crowd in the Haymarket in Chicago" — she joined the cry for vengeance. "They ought to be hanged!" she declared, words over which she agonized for the rest of her life. "For that ignorant, outrageous, blood-thirsty sentence I shall never forgive myself," she confessed on the fourteenth anniversary of the executions, "though I know the dead men would have forgiven me, though I know those who love them forgive me. But my own voice, as it sounded that night, will sound so in my ears till I die — a bitter reproach and shame."

De Cleyre hoped to redeem herself by dedicating her life to opposing the state. A few years later, she converted to individualist anarchism and wrote articles for Benjamin Tucker’s Liberty. This inspired her to use anarchist theory to explain the subjugation of women. In a lecture delivered to the Unity Congregation in Philadelphia, De Cleyre asserted:

“These two things, the mind domination of the Church, and the body domination of the State are the causes of Sex Slavery.”

She argues that religion is the source of the idea that women are inferior to men. Various religious doctrines begin with the idea that it is woman who manipulates man into performing evil. This is most explicitly shown in the story of Adam, where he is persuaded by Eve to disobey God. The church then uses its teachings to manipulate society into believing women must be treated differently because of their “natural” desire to sin. However, the church is powerless without the authority to control women. The bystander may ask: “Why don’t the women leave!” De Cleyre answers:

“Will you tell me where they will go and what they shall do? When the State, the legislators, has given to itself, the politicians, the utter and absolute control of the opportunity to live.”

Thus, the state is the enforcer that subjugates women to the enslavement of men. This led De Cleyre to enact a strike against the institution of marriage itself — interpreting it as the legal extension of the belief that man should rule over woman.

Near the end of her life, her anarchist rival Emma Goldman claimed that De Cleyre had converted to communism; however, this claim is likely untrue. De Cleyre consistently denounced the label communist and wrote many essays against the ideology. In The Individualist And The Communist: A Dialogue, written alongside Rosa Slobodinsky, De Cleyre describes a hypothetical debate between herself and a communist over the issues of free land, free money, and free competition. When the hypothetical communist mockingly labels her the apostle of capitalistic Anarchism, she replies:

“If you choose to call it so. Names are indifferent to me; I am Not afraid of bugaboos. Let it be so then, capitalistic Anarchism”

(Markets Not Capitalism. Edited by Chartier & Johnson. 97).

While she does repudiate her individualism in The Making of an Anarchist, she specifically denounces the notion that she has converted to communism. Instead, she makes the case that any economic system — be it socialism, communism, individualism, or mutualism — is compatible with anarchism as long as it does not rely on coercion. She writes:

“Though I no longer hold the particular economic gospel advocated by Tucker, the doctrine of Anarchism itself, as then conceived, has but broadened, deepened, and intensified itself with years. […] Liberty and experiment alone can determine the best forms of society. Therefore I no longer label myself otherwise than as “Anarchist” simply.”

Thus, Voltairine De Cleyre became one of the early pioneers of anarchism-without-adjectives.

However, the writings of Tucker, Spooner, and De Cleyre were to be overshadowed by another individualist thinker — perhaps the most influential writer of the 19th century: Herbert Spencer.

Herbert Spencer was one of the most popular and influential European philosophers of his time. Raised under a Quaker background, Spencer spent the early part of his career as a railroad draftsmen, where he developed an instinctively distrust of businessmen. He later wrote many works that helped develop the fields of evolution and sociology. Although commonly attributed to Charles Darwin, it was Spencer who coined the praise “Survival of the fittest.” This led the historian Richard Hofstadter to popularize the idea that Spencer was a social Darwinist who misinterpreted Darwin’s ideas on evolution to justify economic and social inequality.

However, contrary to this narrative, Spencer was not a social Darwinist. Recent scholarship by Thomas C. Leonard, Roderick Long, George H. Smith, and Edward N. Zalta, has helped to debunk this false but common notion. To summarize their arguments, the philosopher Matthew Zwolinkski focuses on three main points:

(1) Spencer was a Lamarckian and not a Darwinian in his understanding of evolution. This meant acquired traits were biologically inherited rather than brought about through the chance of natural selection.

“This belief had important implications for Spencer, insofar as it led him to a view of evolution as a progressive phenomenon moving society and the individuals who compose it to higher and better stages of existence.”

(2) Spencer opposed the aggressive use of force.

“the core principle of Spencer’s ethics, his “law of equal freedom,” is explicitly interpreted by Spencer as entailing a prohibition on depriving others of their life or liberty. For Spencer, ethical principles are the product of evolutionary forces, but also serve to put an independent “check” on those forces.”

(3) Spencer supported charity.

“Spencer writes that “in so far as the severity of this process is mitigated by the spontaneous sympathy of men for each other, it is proper that it should be mitigated.” Spencer’s objection, he proceeds to clarify, is not to charity as such, but rather to charity that either a) involves a violation of the law of equal freedom, as does redistribution that is coercively obtained, or b) mitigates present suffering only at the cost of causing greater suffering in the future, as do policies which encourage carelessness by shielding people from the costs of their careless behavior.”

Spencer’s writings are vast. He wrote on issues related to ethics, political philosophy, psychology, biology and sociology. His book, The Principles of Sociology, was an important contribution to the field of sociology for both its method and much of its content.

One of Spencer’s biggest insights was on the topic of social evolution. He thought that social evolution went through four stages: The first being primitive societies characterized by casual political cooperation; The second being militant societies characterized by hierarchical control; The third being industrial societies where centralized political hegemony collapses, giving way to minimally regulated markets; and the fourth being spontaneously, self-regulating, market utopias where government is no longer necessary.

“The more these primal societies crowd each other, the more externally violent and militant they become. Success in war requires greater solidarity and politically consolidated and enforced cohesion. Unremitting warfare fuses and formalizes political control, eradicating societies that fail to consolidate sufficiently. Clans form into nations and tribal chiefs become kings. As militarily successful societies subdue and absorb their rivals, they tend to stabilize and to “compound” and “recompound,” stimulating the division of labor and commerce.

The division of labor and spread of contractual exchange transform successful and established “militant” societies into “negatively regulative industrial” societies prizing individual freedom and basic rights where the state recedes to protecting citizens against force and fraud at home and aggression from abroad. Other things being equal, a society in which life, liberty, and property, are secure, and all interests justly regarded, must prosper more than one in which they are not; and, consequently, among competing industrial societies there must be gradual replacing of those in which personal rights are imperfectly maintained, by those in which they are perfectly maintained”

Although it is not much discussed, Herbert Spencer was a liberal utilitarian, much like John Stuart Mill. Spencer further clarifies this in an 1863 exchange of letters with Mill where he complains that Mill had unfairly labeled him as an anti-utilitarian. He did disagree with the empirical utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham, but advocated what he called rational utilitarianism.

“Responding to T. H. Huxley’s accusation that he conflated good with “survival of the fittest,” Spencer insisted that “fittest” and “best” were not equivalent. He agreed with Huxley that though ethics can be evolutionarily explained, ethics nevertheless preempts normal struggle for existence with the arrival of humans. Humans invest evolution with an “ethical check,” making human evolution qualitatively different from non-human evolution.

“Rational” utilitarianism constitutes the most advanced form of “ethical check[ing]” insofar as it specifies the “equitable limits to his [the individual’s] activities, and of the restraints which must be imposed upon him” in his interactions with others. […] [Like] Sidgwick, [Spencer’s] utilitarian […] reasoning exposes, refines and systematizes our underlying moral intuitions, which have thus far evolved in spite of their under-appreciated utility. Whereas Spencer labeled this progress towards “rational” utilitarianism, Sidgwick more appropriately called this “progress in the direction of a closer approximation to a perfectly enlightened [empirical] Utilitarianism”

All things considered, Spencer could plausibly be described as an individualist anarchist in the tradition of Lysander Spooner. In early editions of Social Statics, Spencer specifically defends the idea of voluntary outlawry — that being the ability of people to drop any and all connection with the state. In an often forgotten part of Social Statics, He includes that

“it is a mistake to assume that government must necessarily last forever. The institution marks a certain stage of civilization – is natural to a particular phase of human development. It is not essential but incidental. As amongst the Bushmen we find a state antecedent to government; so may there be one in which it shall have become extinct.”

On domestic and foreign issues, Spencer was far from what modern readers would describe as “conservative” for his time. Damon Root notes:

“Spencer was an early feminist, advocating the complete legal and social equality of the sexes (and he did so, it's worth noting, nearly two decades before John Stuart Mill's famous On the Subjection of Women first appeared). He was also an anti-imperialist, attacking European colonialists for their deeds of blood and rapine against subjugated races."

In fact, Spencer arguably had more socialistic views than Benjamin Tucker. He argued that the state should nationalize all land and he even supported the elimination of wage labor in favor of worker’s cooperatives. This individualistic radicalism would live on through the works of his disciple Auberon Herbert; but as Spencer got older and his health declined, he began to abandon many of his initial beliefs.

“His doubts about businessmen softened. He joined the homeopathist Lord Elcho in the Liberty and Property Defence League. […] Spencer pulled back from the unorthodoxies of Social Statics. No, he now accepted, people were not free to make themselves “voluntary outlaws,” as no one in practice could deny themselves the state’s protection. No, public ownership of land was neither right in principle nor practicable. No, women should probably not have the vote at once because […] women’s evolutionarily “lower” animal nature prevailed over their “higher” rational side and because […] women would tend to vote for despotic figures of authority. […] Spencer grew less hostile to religion and even began to tolerate babies” (Liberalism. Fawcette. 88).

Following the rising popularity of progressivism and state-socialism, it appeared the new age had little need for his version of liberalism. Even his close friend and protégée, Beatrice Webb, converted to state-socialism and would later help found the Fabian Society. To Spencer, Britain was reverting back to the militant society — which no doubt played a role in fermenting his growing pessimism.

Before his abandonment of radical politics, Spencer sought to explain why so many self-proclaimed liberals were becoming so attracted to the use of state power. In his essay, “The New Toryism”, he argues:

“in the minds of most, a rectified evil is equivalent to an achieved good, […] and the welfare of the many came to be conceived alike by Liberal statesmen and Liberal voters as the aim of Liberalism. Hence the confusion. The gaining of a popular good […] has come to be sought by Liberals, not as an end to be indirectly gained by relaxations of restraints, but as the end to be directly gained. And seeking to gain it directly, they have used methods intrinsically opposed to those originally used.”

He then prophesies a libertarian-conservative alliance:

“A new species of Tory may arise[.] […] The laws made by Liberals are so greatly increasing the compulsions and restraints exercised over citizens, that among Conservatives who suffer from this aggressiveness there is growing up a tendency to resist it [...] So that if the present drift of things continues, it may by and by really happen that the Tories will be defenders of liberties which the Liberals, in pursuit of what they think popular welfare, trample under foot”.

Although it took many more years and occurred in another country, this alliance between conservatives and libertarians would become more relevant than Spencer ever imagined — and it would forever change the way the world understood the political spectrum.